ResNets were considered state-of-the-art CNNs for many tasks in computer vision until the last couple years. In this post, we’ll first walk through the paper that introduced the idea of residual networks, then dive deep into implementing our own ResNets from scratch. We’ll implement our own torch.nn.Modules for each layer and look deep under the hood into manipulating tensors in memory to implement a 2d convolution layer and max pool layer from scratch. Along the way, we’ll learn how to load state from a pretrained ResNet into our custom ResNet and classify some images, as well as fine-tune a ResNet using the Fashion MNIST dataset.

You can choose to follow along directly in Colab for working code:

Table of Contents

- ResNet Paper Walk-Through

- Architecture Implementation From Scratch

- Replacing PyTorch building blocks with our own by subclassing

nn.Module - Finetune for FashionMNIST

ResNet Paper Walk-Through

ResNets were introduced in Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition by Kaiming He, et al. in 2015. The techniques described in the paper were used to achieve 3.57% error on the ImageNet test set, good for 1st place in the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) 2015 classification task.

Motivation

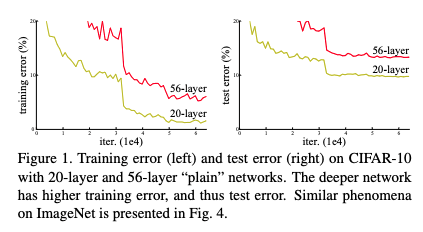

Around that time, there had been breakthroughs in making networks deeper, but only up to a point. Input normalization and batch normalization layers had been introduced to address the vanishing/exploding gradient problem which affected convergence during training. However, after that breakthrough, another problem was discovered: accuracy degradation. This was surprisingly not due to overfitting. As more layers were added, not only would the validation accuracy get worse, the training accuracy would also plateau and then worsen. Some intuition for this surprise is that a deeper network composed of the same layers and weights as a shallower network plus additional identity layers at the end should perform no worse than the shallower network; but this turned out not to be the case in experiments.

Key Idea

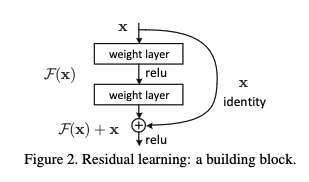

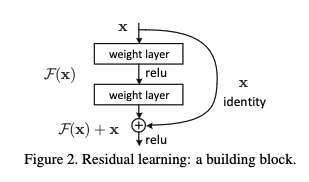

The key idea of the paper was that in order to make networks deeper (and therefore produce better results), the layers can be reformulated into layer blocks and using skip connections, learn a residual function relative to the input to the block. The intuition here was that it would be easier to learn a residual driven to zero rather than learn an identity layer that included nonlinear activations. So instead of trying to learn a function $H(x)$, learn $F(x) = H(x) - x$.

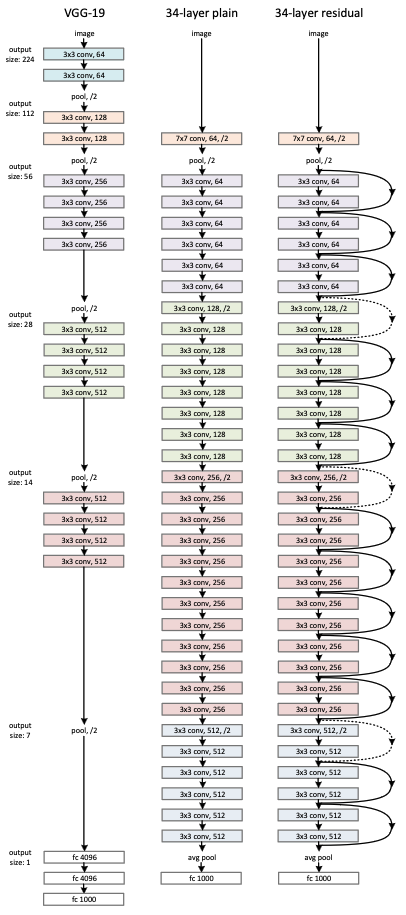

The authors ran experiments comparing “plain” deep networks with the same networks plus skip connections, or “residual networks” (see image below for architecture comparison). The experiments showed

- for plain networks, a deeper architecture had worse error rate than a shallower architecture

- for deeper residual networks, a deeper archtecture had better error rate than a shallower architecture

- for architectures of the same depth, residual networks had better error rate than plain networks

In the image above, on the left is VGG-19, introduced in Very Deep Convolutional Networks For Large Scale Image Recognition. VGG networks were a large improvement on AlexNet, by splitting large convolution kernels into multiple 3x3 kernels, and won the ILSVRC 2014 classification task.

In the middle is a 34-layer plain network and on the right is the same network with skip connections.

Identity vs Projection Shortcuts

In order to add the output of a block ($x$) with the residual from the next block ($F(x,W_i)$), the two dimensions must match (across channel, width, height).

An identity skip connection may be used when the dimensions are already the same size; however, when the dimensions do not match, a linear projection must be applied such that the sum is $F(x,W_i)$ + $W_sx$.

$W_s$ can also be applied to $x$ in the case that dimensions already match but was not found to be essential to help with the degradation problem so it is not applied in the identity mapping for simplicity.

Note the notation used for $W_sx$ is for a linear layer but can be applied for a convolutional layer as well.

Note $F(x,W_i)$ can refer to a block with any number of layers (with activation function in between each layer), but the architectures discussed are with 2 and 3 layers. A single layer would have no extra activation so adding the skip connection would make little difference.

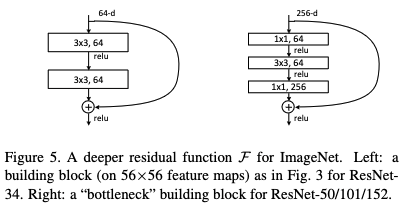

Deeper Bottleneck Architectures

In order to reduce training time for larger and deeper networks, a bottleneck block with 3 layers is used to replace a block with 2 layers. This bottleneck architecture reduces dimensionality when applying the 3x3 convolution kernels, by downsampling the input and upsampling the output.

Experiments

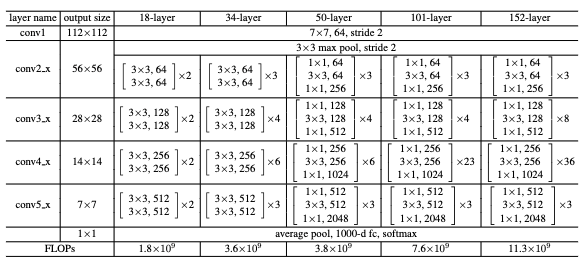

The following table lists the various ResNet architectures that were tried, ranging from an 18-layer network up to one with 152 layers. They each share the same initial and final layers. Varying depths of convolutional blocks are used in the middle.

Batch norm is applied after each convolution layer and before activation with ReLU.

Weights are initialized following the initialization scheme proposed by the same author, Kaiming He.

The 18-layer ResNet architecture is compared with a plain 18-layer architecture to demonstrate a baseline for no significant accuracy improvement at that depth (although converges faster). The 34-layer ResNet has a marked improvement over its corresponding 34-layer plain net. In the 50-layer and up architectures, the conv blocks switch to use the 3-layer bottleneck architectures. Deeper networks achieved better performance on ImageNet.

The residuals of layers were found to be smaller than their plain counterparts.

Note the initial size of each image is cropped to 224x224, hence the resulting output sizes.

The final layer is a 1000-d fully-connected layer for classification on the ImageNet dataset.

Additional experiments were run on CIFAR-10 with architectures that follow the same general design up to >1000 layers. The deepest network still had good results, but performed worse than a network 10x shallower, which they attributed to overfitting.

Architecture Implementation From Scratch

Next, we’ll build our own ResNet architecture from scratch. We’ll design our code to be flexible to the implementations of the building blocks, whether they come from torch.nn or are custom. We’ll design the following in this section:

ConvLayer- Composed of aConv2d,BatchNorm2d, and optionally aReLUactivationConvBlockandConvBlockBottleneck- Composed of twoConvLayers for the former and three for the latterResidualBlock- Adds together the output of aConvBlock(the residual), and either the input to the block or a projection of the input, depending on if downsampling occurred (via striding).BlockGroup- Composed of a sequence ofResidualBlocks. EachBlockGroupcorresponds to aconv{i}_x“layer” fori = {2...5}in the description of each ResNet architecture.ResNet- Puts together theBlockGroups, preprends the input layers, and appends the output layers. AResNetis constructed by specifying the number ofResidualBlocks in eachBlockGroup, the feature dimensions for eachBlockGroup, and the strides for the firstResidualBlocks for eachBlockGroup. The input and output feature dimensions of the network are also specified.

We’ll then test our architecture implementation by making concrete ResNet34 and ResNet50 models using torch.nn layers for Conv2d, BatchNorm2d, etc., and loading pre-trained weights for these models from PyTorch. If our implementation is correct, we should be able to successfully load the weights and achieve the same results when running our models vs. running the corresponding pretrained models.

Note: Much of the code below, and in the following sections, comes from working through ARENA 3.0 exercises and checking the solutions, although the extensions for generality of building blocks and bottleneck architectures are solely my design. The functionality for being able to specify the lower-level building blocks was inspired by C++ templates. If someone knows a better way to do this, please let me know!

Templated ResNet architecture implementation

def Conv2dFactory(Conv2d, BatchNorm2d, ReLU):

class ConvLayer(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_feats, out_feats, kernel_size=3, stride=1, \

padding=1, activation=False, bias=False):

super().__init__()

self.conv = Conv2d(in_feats, out_feats, kernel_size=kernel_size, \

stride=stride, padding=padding, bias=bias)

self.batchnorm2d = BatchNorm2d(out_feats)

self.relu = ReLU()

self.activation = activation

def forward(self, x):

out = self.batchnorm2d(self.conv(x))

if not self.activation:

return out

else:

return self.relu(out)

return ConvLayer

def ConvBlockFactory(ConvLayer, Sequential, bottleneck=False):

class ConvBlock(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_feats, out_feats, middle_feats=None, first_stride=1):

super().__init__()

self.conv_block = Sequential(ConvLayer(in_feats, out_feats, \

stride=first_stride, \

activation=True),

ConvLayer(out_feats, out_feats))

def forward(self, x):

return self.conv_block(x)

'''

Here we make a small deviation from the original paper to follow

https://pytorch.org/vision/main/models/generated/torchvision.models.resnet50.html

which says:

The bottleneck of TorchVision places the stride for downsampling to the

second 3x3 convolution while the original paper places it to the first

1x1 convolution. This variant improves the accuracy and is known as

ResNet V1.5.

'''

class ConvBlockBottleneck(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_feats, out_feats, middle_feats, first_stride=1):

super().__init__()

self.conv_block = Sequential(ConvLayer(in_feats, middle_feats, \

kernel_size=1, \

#stride=first_stride, \

padding=0, activation=True),

ConvLayer(middle_feats, middle_feats, \

stride=first_stride, \

activation=True),

ConvLayer(middle_feats, out_feats,

kernel_size=1, padding=0))

def forward(self, x):

return self.conv_block(x)

if not bottleneck:

return ConvBlock

else:

return ConvBlockBottleneck

def ResidualBlockFactory(ConvBlock, ConvLayer, ReLU):

class ResidualBlock(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_feats, out_feats, middle_feats=None,

first_stride=1):

'''

For compatibility with the pretrained model, the ConvBlock branch is

declared first, and the optional projection is declared second.

'''

super().__init__()

self.left = ConvBlock(in_feats, out_feats, middle_feats, first_stride)

if first_stride > 1 or in_feats != out_feats:

projector = ConvLayer(in_feats, out_feats, kernel_size=1, \

stride=first_stride, padding=0)

self.right = projector

else:

self.right = t.nn.Identity()

self.relu = ReLU()

def forward(self, x):

'''

x: shape (batch, in_feats, height, width)

Return: shape (batch, out_feats, height/first_stride,

width/first_stride)

'''

return self.relu(self.left(x) + self.right(x))

return ResidualBlock

def BlockGroupFactory(ResidualBlock, Sequential):

class BlockGroup(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_blocks, in_feats, out_feats, middle_feats=None,

first_stride=1):

'''

An n_blocks-long sequence of ResidualBlock where only the first block

uses the provided stride.

'''

super().__init__()

blocks = [ResidualBlock(in_feats, out_feats, middle_feats=middle_feats, \

first_stride=first_stride)] + \

[ResidualBlock(out_feats, out_feats, middle_feats=middle_feats) \

for i in range(n_blocks - 1)]

self.block_group = Sequential(*blocks)

def forward(self, x):

'''

x: shape (batch, in_feats, height, width)

Return: shape (batch, out_feats, height/first_stride,

width/first_stride)

'''

return self.block_group(x)

return BlockGroup

def ResNetFactory(ConvLayer, MaxPool2d, BlockGroup, AveragePool, Flatten, \

Linear, Sequential):

class ResNet(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

input_channels = 3,

n_blocks_per_group=[3, 4, 6, 3],

middle_features_per_group=None,

out_features_per_group=[64, 128, 256, 512],

first_strides_per_group=[1, 2, 2, 2],

n_classes=1000,

):

super().__init__()

self.n_blocks_per_group = n_blocks_per_group

self.middle_features_per_group = middle_features_per_group

self.out_features_per_group = out_features_per_group

self.first_strides_per_group = first_strides_per_group

self.n_classes = n_classes

in_features_per_group = [64] + out_features_per_group[:-1]

if middle_features_per_group is None:

middle_features_per_group = [None] * len(in_features_per_group)

self.input_layers = Sequential(ConvLayer(input_channels, 64, \

kernel_size=7, stride=2, \

padding=3, activation=True),

MaxPool2d(kernel_size=3, stride=2, \

padding=1))

args_per_group = [n_blocks_per_group, in_features_per_group, \

out_features_per_group, middle_features_per_group, \

first_strides_per_group]

self.block_groups = Sequential(*(BlockGroup(*args) \

for args in zip(*args_per_group)))

self.output_layers = Sequential(AveragePool(), Flatten(), \

Linear(out_features_per_group[-1], \

n_classes))

def forward(self, x):

'''

x: shape (batch, channels, height, width)

Return: shape (batch, n_classes)

'''

x = self.input_layers(x)

x = self.block_groups(x)

x = self.output_layers(x)

return x

return ResNet

Make concrete ResNet34 and ResNet50 architectures using PyTorch layers

From our templated ResNet architecture, we can construct any of the five ResNet architectures using torch.nn building blocks. Here we’ll construct a ResNet34 and a ResNet50 so we can test out both types of ConvBlocks. ResNet34 does not have the bottleneck design while ResNet50 does.

All layers have a PyTorch implementation, except a global average pool over all spatial dimensions. We can easily implement that from scratch:

class AveragePool(t.nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

return t.mean(x, dim=(2,3)) # Average over all spatial dims

Now we can create a concrete ResNet34 architecture with torch.nn layers and the classes we’ve defined.

Conv2dLayer = Conv2dFactory(t.nn.Conv2d, t.nn.BatchNorm2d, t.nn.ReLU)

ConvBlock = ConvBlockFactory(Conv2dLayer, t.nn.Sequential)

ResidualBlock = ResidualBlockFactory(ConvBlock, Conv2dLayer, t.nn.ReLU)

BlockGroup = BlockGroupFactory(ResidualBlock, t.nn.Sequential)

ResNet = ResNetFactory(Conv2dLayer, t.nn.MaxPool2d, BlockGroup, AveragePool, \

t.nn.Flatten, t.nn.Linear, t.nn.Sequential)

my_resnet34 = ResNet() # default arguments correspond to ResNet34

Similarly, here’s a concrete ResNet50 architecture. Recall that ResNet50 and up use the bottleneck design.

BottleneckConvBlock = ConvBlockFactory(Conv2dLayer, t.nn.Sequential, bottleneck=True)

ResidualBlock = ResidualBlockFactory(BottleneckConvBlock, Conv2dLayer, t.nn.ReLU)

BlockGroup = BlockGroupFactory(ResidualBlock, t.nn.Sequential)

ResNet = ResNetFactory(Conv2dLayer, t.nn.MaxPool2d, BlockGroup, AveragePool, \

t.nn.Flatten, t.nn.Linear, t.nn.Sequential)

my_resnet50 = ResNet(n_blocks_per_group=[3, 4, 6, 3],

middle_features_per_group=[64, 128, 256, 512],

out_features_per_group=[256, 512, 1024, 2048])

Test the implementation

We can check whether our architecture has the right size by attempting to copy weights from a pretrained model into our model. We use PyTorch’s pretrained models.

# Copied verbatim from https://github.com/callummcdougall/ARENA_3.0/blob/main/chapter0_fundamentals/exercises/part2_cnns/solutions.py#L548-L565

def copy_weights(my_resnet, pretrained_resnet):

'''Copy over the weights of `pretrained_resnet` to your resnet.'''

# Get the state dictionaries for each model, check they have the same number of parameters & buffers

mydict = my_resnet.state_dict()

pretraineddict = pretrained_resnet.state_dict()

assert len(mydict) == len(pretraineddict), "Mismatching state dictionaries."

# Define a dictionary mapping the names of your parameters / buffers to their values in the pretrained model

state_dict_to_load = {

mykey: pretrainedvalue

for (mykey, myvalue), (pretrainedkey, pretrainedvalue) in zip(mydict.items(), pretraineddict.items())

}

# Load in this dictionary to your model

my_resnet.load_state_dict(state_dict_to_load)

return my_resnet

pretrained_resnet34 = t.hub.load('pytorch/vision:v0.10.0', 'resnet34', pretrained=True)

my_resnet34 = copy_weights(my_resnet34, pretrained_resnet34)

print_param_count(my_resnet34, pretrained_resnet34)

Model 1, total params = 21797672

Model 2, total params = 21797672

All parameter counts match!

pretrained_resnet50 = t.hub.load('pytorch/vision:v0.10.0', 'resnet50', pretrained=True)

my_resnet50 = copy_weights(my_resnet50, pretrained_resnet50)

print_param_count(my_resnet50, pretrained_resnet50)

Model 1, total params = 25557032

Model 2, total params = 25557032

All parameter counts match!

Classify some RGB images

Helper functions

We follow https://pytorch.org/hub/pytorch_vision_resnet/ for preprocessing images, using a pretrained model (as we did in the previous section), and looking up human-readable classes from model predictions.

preprocess = transforms.Compose([

transforms.Resize(256),

transforms.CenterCrop(224),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize(mean=[0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std=[0.229, 0.224, 0.225]),

])

def predict_top5(model, image_filenames):

model.eval()

images = [PIL.Image.open(filename) for filename in image_filenames]

input_batch = t.stack([preprocess(img) for img in images], dim=0)

# move the input and model to GPU for speed if available

if t.cuda.is_available():

input_batch = input_batch.to('cuda')

model.to('cuda')

# run the model

with t.no_grad():

output = model(input_batch)

probabilities = t.nn.functional.softmax(output, dim=1)

# Read the categories

with open("imagenet_classes.txt", "r") as f:

categories = [s.strip() for s in f.readlines()]

# Show top categories per image

top5_prob, top5_catid = t.topk(probabilities, k=5)

for i in range(top5_prob.size(0)):

display(images[i])

for j in range(top5_prob.size(1)):

print(categories[top5_catid[i][j]], top5_prob[i][j].item())

print()

Even though two models can have the same parameters, that doesn’t mean the architectures are identical. Things like where a stride is taken in a BlockGroup can have an impact on model output. We can check the equality of two models by checking the equality of their outputs.

Classify some images and compare outputs

We imported some images during the “Install dependencies” step (in the Colab notebook) and can use them here. Now we can classify some images to check our architecture implementation. Within a tolerance of 1e-5 due to different ways of chaining floating point operations, we are able to verify that the custom models produces the same predictions as the pretrained models.

Test ResNet34

compare_predictions(my_resnet34, pretrained_resnet34, IMAGE_FILENAMES, 1e-5)

Models are equivalent!

Test ResNet50

compare_predictions(my_resnet50, pretrained_resnet50, IMAGE_FILENAMES, 1e-5)

Models are equivalent!

Let’s also see what the top 5 predicted classes are for each image, just for fun.

predict_top5(my_resnet50, IMAGE_FILENAMES)

golden retriever 0.9919309020042419

Brittany spaniel 0.0028146819677203894

Labrador retriever 0.0012666297843679786

tennis ball 0.0006666457047685981

kuvasz 0.0005991900688968599

brown bear 0.9999508857727051

American black bear 4.4745906052412465e-05

ice bear 3.734054644155549e-06

sloth bear 5.089370347377553e-07

bison 4.709042400463659e-08

suspension bridge 0.6104913353919983

pier 0.3443833291530609

steel arch bridge 0.02683708816766739

promontory 0.009572144597768784

viaduct 0.0035211530048400164

obelisk 0.6610313653945923

megalith 0.10190818458795547

pole 0.06568432599306107

totem pole 0.024245884269475937

fountain 0.0200052410364151

streetcar 0.9358044266700745

trolleybus 0.06182621046900749

passenger car 0.0013690213672816753

electric locomotive 0.000848782598040998

bullet train 3.628083140938543e-05

Replacing PyTorch building blocks with our own by subclassing nn.Module

torch.nn Modules are stateful building blocks that implement the forward pass of a computation (by implementing forward()) and partner with PyTorch’s autograd system for the backward pass. Parameters to be learned in a module are specified by wrapping their tensors in a torch.nn.Parameter, which automatically registers them with the module to be updated by forward/backward passes.

All modules should subclass torch.nn.Module to be composable with other modules. The submodules of a module can be accessed via calls to children() or named_children(). To be able to recursively access all the submodules’ children, call modules() or named_modules().

In order to dynamically define submodules ModuleList or ModuleDict can be used to register submodules from a list or a dict. Another way is what we did above, with Sequential(*args).

parameters() or named_parameters() can be used to recursively access all parameters of a module and its submodules.

A general function to recursively apply any function to a module and its submodules is apply().

Modules have a training mode and evaluation mode, which can be toggled between with train() and eval(). Some modules, like BatchNorm2d, have different behavior depending on its modality.

A trained model’s state can be saved to disk by calling its state_dict() and loaded with load_state_dict().

State includes not only modules’ parameters, but also any “persistent buffers” for non-learnable aspects of computation, like the running mean and variance in a BatchNorm2d layer. Non-persistent buffers are not saved. Buffers can be registered via register_buffer(), which marks them as persistent by default. Buffers can be accessed recursively, unsurprisingly at this point, with buffers() or named_buffers().

For more details and other features of torch.nn.Module, consult https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/notes/modules.html.

Implementing our own modules with torch.nn.Module

class CustomReLU(t.nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

return t.maximum(x, t.tensor(0.))

class CustomLinear(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_features, out_features, bias=True):

'''

A simple linear (technically, affine) transformation.

The fields should be named `weight` and `bias` for compatibility with

PyTorch.

'''

super().__init__()

self.in_features = in_features

self.out_features = out_features

weight = 2*(t.rand(out_features, in_features) - 0.5) / \

t.sqrt(t.tensor(in_features))

self.weight = t.nn.Parameter(weight)

if bias:

b = 2*(t.rand(out_features) - 0.5) / t.sqrt(t.tensor(in_features))

self.bias = t.nn.Parameter(b)

else:

self.bias = None

def forward(self, x):

'''

x: shape (*, in_features)

Return: shape (*, out_features)

'''

sum = einops.einsum(x, self.weight, \

'... in_features, out_features in_features -> \

... out_features')

if self.bias is not None:

sum += self.bias

return sum

def extra_repr(self):

return f"in_features={self.in_features}, \

out_features={self.out_features}, bias={self.bias is not None}"

class CustomFlatten(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, start_dim=1, end_dim=-1):

super().__init__()

self.start_dim = start_dim

self.end_dim = end_dim

def forward(self, input):

'''

Flatten out dimensions from start_dim to end_dim, inclusive of both.

'''

shape = t.tensor(input.shape)

end_dim = self.end_dim if self.end_dim >=0 else len(shape) + self.end_dim

flattened_dim = t.prod(shape[self.start_dim:end_dim+1])

flattened_shape = list(input.shape[:self.start_dim]) + \

[int(flattened_dim)] + list(input.shape[end_dim+1:])

return t.reshape(input, flattened_shape)

def extra_repr(self):

return ", ".join([f"{key}={getattr(self, key)}" for key in \

["start_dim", "end_dim"]])

class CustomSequential(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, *modules):

super().__init__()

for index, mod in enumerate(modules):

self._modules[str(index)] = mod

def __getitem__(self, index):

index %= len(self._modules) # deal with negative indices

return self._modules[str(index)]

def __setitem__(self, index, module):

index %= len(self._modules) # deal with negative indices

self._modules[str(index)] = module

def forward(self, x):

'''

Chain each module together, with the output from one feeding into

the next one.

'''

for mod in self._modules.values():

x = mod(x)

return x

class CustomBatchNorm2d(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_features, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1):

'''

Like nn.BatchNorm2d with track_running_stats=True and affine=True.

Name the learnable affine parameters `weight` and `bias` in that order.

'''

super().__init__()

self.weight = t.nn.Parameter(t.ones(num_features))

self.bias = t.nn.Parameter(t.zeros(num_features))

self.momentum = momentum

self.eps = eps

self.num_features = num_features

self.register_buffer('running_mean', t.zeros(num_features))

self.register_buffer('running_var', t.ones(num_features))

self.register_buffer('num_batches_tracked', t.tensor(0))

def forward(self, x):

'''

Normalize each channel.

x: shape (batch, channels, height, width)

Return: shape (batch, channels, height, width)

'''

if self.training:

mean = t.mean(x, dim=(0, 2, 3), keepdim=True)

var = t.var(x, unbiased=False, dim=(0, 2, 3), keepdim=True)

self.running_mean = \

(1 - self.momentum) * self.running_mean + self.momentum * mean.squeeze()

self.running_var = \

(1 - self.momentum) * self.running_var + self.momentum * var.squeeze()

self.num_batches_tracked += 1

else:

mean = einops.rearrange(self.running_mean, 'c -> 1 c 1 1')

var = einops.rearrange(self.running_var, 'c -> 1 c 1 1')

weight = einops.rearrange(self.weight, 'c -> 1 c 1 1')

bias = einops.rearrange(self.bias, 'c -> 1 c 1 1')

return ((x - mean) / (var + self.eps).sqrt()) * weight + bias

def extra_repr(self):

keys = ['num_features', 'eps', 'momentum']

return ", ".join([f'{key}={getattr(self, key)}' for key in keys])

For Conv2d and MaxPool2d, we’ll cheat a little and use the preimplemented PyTorch nn.functionals for now. Implementing these further from scratch will be covered in the next section.

def CustomConv2dFactory(conv2d):

class CustomConv2d(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(

self, in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size, stride=1, padding=0, \

bias=False):

'''

Same as torch.nn.Conv2d with bias=False.

Name your weight field `self.weight` for compatibility with the PyTorch version.

'''

super().__init__()

self.in_channels = in_channels

self.out_channels = out_channels

self.kernel_size = kernel_size

self.stride = stride

self.padding = padding

sqrt_in = t. sqrt(t.tensor(in_channels * kernel_size**2))

weight = ((2 * t.rand(out_channels, in_channels, \

kernel_size, kernel_size)) - 1) / sqrt_in

self.weight = t.nn.Parameter(weight)

self.stride = stride

self.padding = padding

def forward(self, x):

return conv2d(x, self.weight, stride=self.stride, padding=self.padding)

def extra_repr(self) -> str:

keys = ["in_channels", "out_channels", "kernel_size", "stride", "padding"]

return ", ".join([f"{key}={getattr(self, key)}" for key in keys])

return CustomConv2d

def CustomMaxPool2dFactory(maxpool2d):

class CustomMaxPool2d(t.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, kernel_size: int, stride = None, padding: int = 1):

super().__init__()

self.kernel_size = kernel_size

self.stride = stride

self.padding = padding

def forward(self, x):

return maxpool2d(x,self.kernel_size, self.stride, padding=self.padding)

def extra_repr(self):

keys = ["kernel_size", "stride", "padding"]

return ", ".join([f"{key}={getattr(self,key)}" for key in keys])

return CustomMaxPool2d

CustomConv2d = CustomConv2dFactory(t.nn.functional.conv2d)

CustomMaxPool2d = CustomMaxPool2dFactory(t.nn.functional.max_pool2d)

Construct and test ResNet50 using these building blocks

Conv2dLayer = Conv2dFactory(CustomConv2d, CustomBatchNorm2d, CustomReLU)

BottleneckConvBlock = ConvBlockFactory(Conv2dLayer, CustomSequential, bottleneck=True)

ResidualBlock = ResidualBlockFactory(BottleneckConvBlock, Conv2dLayer, CustomReLU)

BlockGroup = BlockGroupFactory(ResidualBlock, CustomSequential)

ResNet = ResNetFactory(Conv2dLayer, CustomMaxPool2d, BlockGroup, AveragePool, \

CustomFlatten, CustomLinear, CustomSequential)

my_resnet50 = ResNet(n_blocks_per_group=[3, 4, 6, 3],

middle_features_per_group=[64, 128, 256, 512],

out_features_per_group=[256, 512, 1024, 2048])

my_resnet50 = copy_weights(my_resnet50, pretrained_resnet50)

print_param_count(my_resnet50, pretrained_resnet50)

Model 1, total params = 25557032

Model 2, total params = 25557032

All parameter counts match!

compare_predictions(my_resnet50, pretrained_resnet50, IMAGE_FILENAMES, atol=1e-5)

Models are equivalent!

Convolutions and MaxPool from Scratch

We’ll take a look under the hood and see how some very low-level operations are performed using torch.as_strided(). This is not something that we’ll need for implementing various architectures in the future - we can simply use PyTorch modules or write our own at the abstraction level used in the previous sections. However, this is useful for getting a much better understanding of how these operations work.

Here is some useful reading to get an understanding of how torch.as_strided() works:

- Using .as_strided for creating views of NumPy arrays

- as_strided and sum are all you need (…to implement the non-pointwise operations in a neural network)

The key thing to understand is the underlying representation of tensors is that the tensors do not take on their shapes in memory. Rather, they live in 1D contiguous arrays (or non-contiguous if the tensor was created by striding over a continuous array).

Here’s some simple matrix operations to get used to torch.as_strided.

trace

Let’s assume this matrix lives in contiguous memory.

def as_strided_trace(mat: Float[Tensor, "i j"]) -> Float[Tensor, ""]:

'''

Similar to `torch.trace`, using only 'as_strided` and `sum` methods.

'''

assert mat.shape[0] == mat.shape[1]

len = mat.shape[0]

return mat.as_strided((1, len), (1, len + 1)).sum(1)

matrix-vector multiplication

def as_strided_mv(mat: Float[Tensor, "i j"], vec: Float[Tensor, "j"]) -> Float[Tensor, "i"]:

'''

Similar to `torch.matmul`, using only `as_strided` and `sum` methods.

'''

return (mat * vec.as_strided(mat.shape, (0,vec.stride()[0]))).sum(1)

matrix-matrix multiplication

def as_strided_mm(matA: Float[Tensor, "i j"], matB: Float[Tensor, "j k"]) -> Float[Tensor, "i k"]:

'''

Similar to `torch.matmul`, using only `as_strided` and `sum` methods.

'''

assert(matA.shape[1] == matB.shape[0])

i,j = matA.shape

j,k = matB.shape

A = matA.as_strided((i,j,k), (matA.stride(0), matA.stride(1), 0))

B = matB.as_strided((i,j,k), (0, matB.stride(0), matB.stride(1)))

return (A*B).sum(1)

conv2d

Check out the Colab notebook for building up slowly to the full implementation of conv2d. We simply present it here.

def conv2d(

x: Float[Tensor, "b ic h w"],

weights: Float[Tensor, "oc ic kh kw"],

stride: IntOrPair = 1,

padding: IntOrPair = 0

) -> Float[Tensor, "b oc oh ow"]:

'''

Like torch's conv2d using bias=False

x: shape (batch, in_channels, height, width)

weights: shape (out_channels, in_channels, kernel_height, kernel_width)

Returns: shape (batch, out_channels, output_height, output_width)

'''

b, ic, h, w = x.shape

oc, ic2, kh, kw = weights.shape

assert(ic == ic2)

pad_h, pad_w = force_pair(padding)

padded_height = h+pad_h*2

padded_width = w+pad_w*2

padded_x = x.new_full(size=(b, ic, padded_height, padded_width), fill_value=0)

padded_x[..., pad_h:h+pad_h, pad_w:w+pad_w] = x

stride_h, stride_w = force_pair(stride)

oh = int((padded_height - kh)/stride_h) + 1

ow = int((padded_width - kw)/stride_w) + 1

new_size = (b, ic, oh, ow, kh, kw)

b_s, ic_s, h_s, w_s = padded_x.stride()

new_stride = (b_s, ic_s, h_s*stride_h, w_s*stride_w, h_s, w_s)

strided_padded_x = padded_x.as_strided(size=new_size, stride=new_stride)

return einops.einsum(strided_padded_x, weights, 'b ic oh ow kh kw, oc ic kh kw -> b oc oh ow')

maxpool2d is very similar to conv2d, except the operations at the end. Max pooling is very similar to convolution in that we slide a window across a matrix, except instead of multiplying by the kernel and summing, we simply take the maximum in the window. Also, instead of having each output channel be a function of all the input channels, we have the same number of output channels as input channels since the max pooling operation is taken independently for each channel.

We can check that replacing the nn.functional versions of conv2d and maxpool2d with these in our custom modules yields the same working ResNet architectures. We do so in the Colab notebook.

Whew! This was a lot of code. But we’ve reached the end of implementing our own ResNet from scratch!

We followed the original paper for the high-level ResNet architectures (and upgraded to the “1.5 version” for the bottleneck design to match with PyTorch’s architecture). We first made concrete models by using building blocks from PyTorch’s torch.nn modules, then replaced them with our own modules by sub-classing torch.nn.Module. Then we went even deeper, using .as_strided() and .sum() to replace torch.nn.functional calls. Along the way, we tested the models by copying weights from PyTorch’s pre-trained ResNet models and running them on some test images to see if we got the same results (modulo some tolerance due to how floating point operations were chained).

Finetune for FashionMNIST

Now let’s do some transfer learning. We should be able to take our pre-trained model (trained on ImageNet with RGB images and 1000 classes) and adapt it to be able to classify images from the FashionMNIST dataset (grayscale images and 10 classes).

We want to change the last layer of our model to output 10 classes instead of 1000 and freeze the weights of all the preceding layers.

For the input, since we want to deal with a single input channel rather than three, we could modify the first layer to take in only a single channel, but it’d be difficult to know which kernels for the three channels to discard. We could try to learn the first layer’s weights from scratch, but let’s try duplicating our single channel input into three channels instead.

As part of adapting our model and data to play nice with each other, we need to resize each image from (1, 28, 28) to (3, 224, 224), the image shape that ResNet34 expects.

transform = transforms.Compose([transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Resize((224, 224)),

transforms.Lambda(lambda x:

einops.repeat(x, '1 h w -> 3 h w'))])

train_dataset = FashionMNIST(root='fashion_mnist', train=True, download=True,

transform=transform)

test_dataset = FashionMNIST(root='fashion_mnist', train=False, download=True,

transform=transform)

train_data = Subset(train_dataset, t.arange(int(len(train_dataset)*0.8)))

valid_data = Subset(train_dataset, t.arange(int(len(train_dataset)*0.8),

len(train_dataset)))

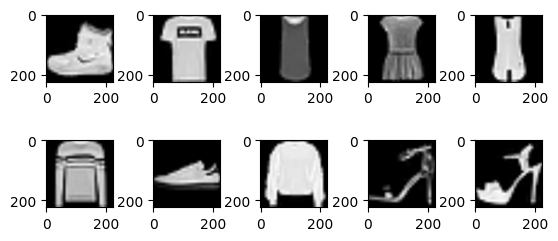

Let’s visualize some of our transformed data.

for i in range(10):

plt.subplot(2, 5, i + 1)

image = einops.rearrange(train_data[i][0], 'c h w -> h w c')

plt.imshow(image, cmap=plt.get_cmap('gray'))

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.6, bottom=0.4)

plt.show()

Now, let’s freeze the weights of our pre-trained model and change the output head to one that outputs 10 logits instead of 1000. We’ll be training the weights of only the final layer.

my_resnet34.requires_grad_(False)

my_resnet34.output_layers[-1] = CustomLinear(

my_resnet34.out_features_per_group[-1], 10)

Let’s reuse the Learner and DataLoaders classes we implemented in Getting Hands On With ML: MNIST. We make some small updates to a) wrap iterating through the training data with tqdm since training will take a lot longer with a bigger model, b) move model and data to device, since we’ll want to use a GPU if available, and c) add gradient accumulation just in case we run out of memory working with large batch sizes.

bs = 64

train_dataloader = DataLoader(train_data, batch_size=bs, shuffle=True, drop_last=True)

valid_dataloader = DataLoader(valid_data, batch_size=bs, drop_last=True)

test_dataloader = DataLoader(test_dataset, batch_size=bs, drop_last=True)

dls = DataLoaders(train_dataloader, valid_dataloader)

epochs = 3

optimizer = t.optim.Adam(my_resnet34.parameters(), lr=1e-3)

loss_func = t.nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

scheduler = t.optim.lr_scheduler.OneCycleLR(

optimizer, max_lr=1e-2, steps_per_epoch=len(train_dataloader), epochs=epochs)

learner = Learner(

dls, my_resnet34.to(device), optimizer, loss_func, accuracy, scheduler,

gradient_accumulation_batch_size=64)

learner.fit(epochs)

0%| | 0/3 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

0%| | 0/750 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

avg training loss: tensor(0.9040, device='cuda:0', grad_fn=<DivBackward0>)

avg validation loss: tensor(1.2077, device='cuda:0')

metric: tensor(0.7381, device='cuda:0')

0%| | 0/750 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

avg training loss: tensor(0.7149, device='cuda:0', grad_fn=<DivBackward0>)

avg validation loss: tensor(0.4802, device='cuda:0')

metric: tensor(0.8446, device='cuda:0')

0%| | 0/750 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

avg training loss: tensor(0.4177, device='cuda:0', grad_fn=<DivBackward0>)

avg validation loss: tensor(0.3967, device='cuda:0')

metric: tensor(0.8632, device='cuda:0')

We can see that we can achieve 86% accuracy on the validation data after 3 epochs.

Cool! We’ve successfully finetuned a ResNet34 model, via feature extraction, to classify FashionMNIST images. We could probably achieve much better results if we didn’t freeze the weights or if we trained a model from scratch (perhaps with a single input channel).

Hopefully you’ve gotten a much better understanding of what a ResNet is and how to work with them after reading this post.

Other Resources

Other resources that I’ve found helpful in aiding my understanding of CNNs and ResNets are linked below: